In the intricate world of papermaking, achieving the desired sheet dryness and quality hinges significantly on the performance of the press section. It's a critical stage where mechanical pressure is applied to remove water from the fibrous web, drastically reducing the energy required later in the drying section. At the heart of many press configurations, particularly in older or specialized machines, lies the top press roller. And among these, the top press stone roller has a storied history and unique characteristics that make it a subject of considerable interest and importance. Understanding its role, properties, and limitations is key to appreciating the evolution and challenges of modern papermaking technology. To be honest, while modern materials have emerged, the principles learned from the stone roller remain relevant.

The press section's primary objective is to remove as much water as possible from the paper web before it enters the dryers. Think about it: water removal through pressing uses mechanical energy, which is vastly more efficient than using thermal energy in the dryers. A typical paper web entering the press section might be 70-80% water, and the goal is to reduce this to 55-65% or even lower, depending on the grade of paper and the press configuration. This seemingly simple task involves complex interactions between the paper web, felt, and rollers under significant pressure. Effective dewatering in this stage not only saves energy but also impacts paper properties like density, smoothness, and strength. The type and surface characteristics of the rollers, especially the top press roller which often makes the initial contact or forms a key nip, play a crucial role in this delicate balance of dewatering and preserving sheet integrity.

Specifically focusing on the top press roller, its position in the press nip is paramount. It's often the upper roller in a press configuration, pressing down onto the paper web supported by a felt, which in turn is often supported by a bottom roll (which might be a suction roll, plain roll, or grooved roll). The top roller's surface comes into direct contact with the top side of the paper web. This direct contact means its surface properties are critical. It must apply pressure evenly across the web width while allowing water to escape from the sheet and felt without causing damage or excessive sheet disturbance. The material and condition of this roller significantly influence the amount of water removed in the nip and the final characteristics of the paper web as it exits the press section. Have you ever considered how the surface texture of a roller could impact the final product you hold in your hands?

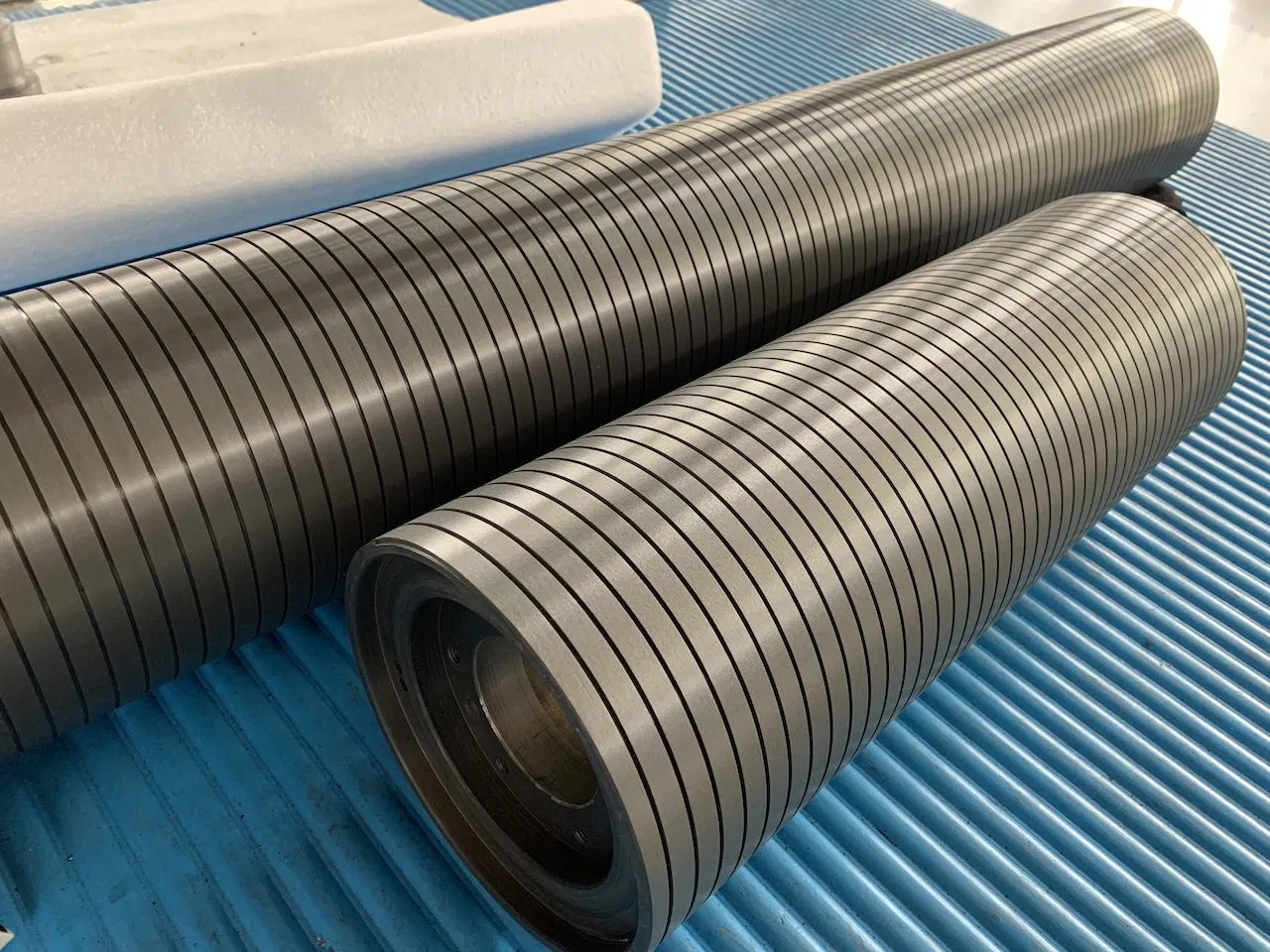

Historically, and in certain applications even today, granite or other types of natural stone were the materials of choice for the top press roller. Why stone? Natural granite, with its inherent hardness and microscopic porosity, offered unique advantages. The texture of the stone, if prepared correctly, provided a surface that could apply pressure firmly while allowing small amounts of water to be absorbed or channeled away from the immediate nip point. This porosity helped prevent the crushing of the paper sheet under high pressure, particularly with certain paper grades. Interestingly enough, different types of granite offered varying degrees of porosity and hardness, allowing machine builders and papermakers to select stone suited for specific applications or paper types. While modern materials can replicate some of these properties, the natural variation and performance of high-quality granite were, for a long time, unmatched.

The benefits derived from using a stone roller in the top press position were manifold, particularly in earlier press designs. One significant advantage was its ability to facilitate water drainage. While the bulk of the water removal occurred through the felt and bottom roll mechanism (like suction or grooves), the stone's surface characteristics aided in preventing water from being hydraulically "trapped" at the top surface of the sheet. This reduced the risk of sheet crushing or "checking" (tiny ruptures in the sheet surface caused by hydraulic pressure). Furthermore, the surface texture of the stone provided a certain degree of grip on the felt and web, helping to maintain sheet runnability and prevent slippage in the nip. Many experts agree that for specific paper grades, the gentle yet firm pressing action provided by a stone roller was ideal for preserving bulk and porosity.

However, using stone rollers also presented significant challenges. Frankly speaking, stone is brittle. It is susceptible to damage from hard foreign objects that might accidentally enter the nip. A small bolt or even a hard knot in the pulp could cause chipping or cracking, requiring costly repairs or replacement. Wear was another issue; the abrasive nature of the paper stock and felt could slowly wear down the stone surface, requiring periodic grinding to maintain flatness and surface finish. Maintaining the correct crown (the precise curvature of the roll surface) on a stone roller was also a skilled and time-consuming process. Furthermore, stone rollers are incredibly heavy, posing challenges for installation, removal, and machine load-bearing structures. These factors contributed to the development of alternative roller materials and designs over time.

As technology advanced, engineers sought to overcome the limitations of natural stone rollers. This led to the development of synthetic stone composites and, more commonly, rubber or polyurethane covers applied to metal cores. These modern materials offer advantages like greater resistance to damage, easier maintenance, lighter weight, and the ability to engineer specific surface properties (like hardness, grooving patterns, or surface texture) with high precision. Some modern press configurations eliminate the need for a dense top roll altogether, using felt-to-felt nips or shoe presses. Yet, even with these advancements, the principles of surface interaction, water handling in the nip, and pressure distribution, which were extensively studied and optimized for stone rollers, remain fundamental to press section design. In some niche applications or for historical machine preservation, stone rollers are still in use or their properties are emulated by modern coverings. It's worth noting that the shift wasn't just about material; it was about evolving press technology as a whole.

Selecting the appropriate top press roller is a decision driven by numerous factors related to the specific paper machine and the grade of paper being produced. Machine speed, nip pressure requirements, the type of felt used, and the desired properties of the final paper sheet all play a role. For example, very absorbent grades might benefit from a porous or textured top roll surface to handle water efficiently. High-speed machines require rollers that can withstand intense dynamic forces and prolonged operation without excessive wear or maintenance. While stone rollers might be less common in high-speed, high-load modern presses compared to composite or covered rolls, understanding their specific advantages in certain conditions helps illuminate the trade-offs involved in roller material selection. It prompts us to ask: what specific interaction is needed between the top roll and the paper web for this particular product?

Proper maintenance is paramount for ensuring the longevity and performance of any press roller, including traditional stone rollers. This involves regular inspection for signs of wear, chipping, or cracking. The surface crown needs to be checked and reground periodically to ensure uniform pressure across the web width. Cleaning is also essential to prevent build-up of fibers or additives that could affect the surface properties or cause uneven wear. While natural stone rollers require specialized grinding equipment and expertise, their durable nature, if properly cared for, allowed them to remain in service for many years. The discipline of maintaining stone rollers provided valuable lessons that are applied to the care of modern covered rolls, emphasizing the importance of surface condition and roller geometry.

Considering practical applications, a top press stone roller might still be found on machines producing specialty papers where a particular surface finish or bulk is desired, or on older machines that are well-maintained and where the original stone roller's performance characteristics are deemed suitable. Their robustness against certain chemical environments might also make them preferable in some niche processes compared to certain polymer covers. While not the default choice in most new high-speed commodity paper machines, their continued presence in specific segments of the industry underscores their unique functional properties and the legacy of papermaking technology. I've found that papermakers operating these machines often have a deep appreciation for the specific nuances and handling required for stone rolls.

In conclusion, the top press stone roller represents a significant chapter in the history of paper machine technology. Its natural properties, such as porosity and hardness, offered key advantages in water removal and sheet handling in the press section, contributing significantly to the efficiency of papermaking for many decades. While modern materials and press designs have evolved, the fundamental challenges of applying pressure, removing water, and maintaining sheet quality in the press nip were largely addressed and understood through the widespread use and optimization of stone rollers. Their characteristics influenced subsequent roller material developments and press configurations. The lessons learned from working with stone continue to inform how we design and operate press sections today, highlighting the enduring principles of mechanical dewatering.

For more detailed information, please visit our official website: Press Stone Roller